2025/10/06

1.なぜ人は叱ってしまうのか?

なぜ人間は自分の子供や他の人を叱ってしまうのだろうか?その理由は、叱るという行為が、相手の行動を変えるということに対して非常に強い力を発揮してしまうからだ。この強力な効果のことをNegativity Bias(ネガティビティ・バイアス)という。例えば、1万円もらえるというポジティブな出来事と、1万円失うというネガティブな出来事があったとする。同じ1万円という金額なのだから、感情への影響の強さは同じように思う(嬉しい・悲しいという感情のタイプは別として)。しかし、実際には1万円失うというネガティブな出来事の方が、1万円もらえるというポジティブな出来事よりもより大きな感情を発生させるということがわかっている。このようにネガティブな出来事の方が強い効力を発揮することをNegativity Biasという。

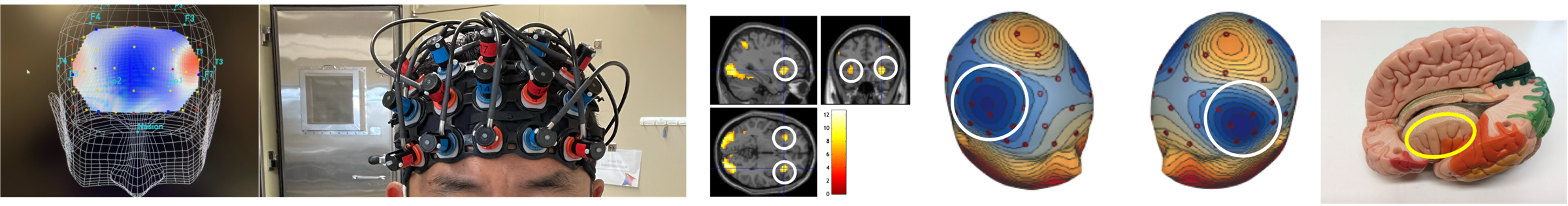

fMRIという脳の活動を「見える化」する装置を用いた私たちの実験でも、叱るといったネガティブな刺激は、脳の情動中枢(これを扁桃体という)をより強くそして早く活動させることが示されている。一方で、褒めるというポジティブな刺激は、弱くしかもゆっくりと情動中枢を活性化させることがわかった。このように、叱るというネガティブな情報は、人間の情動中枢を強くそして早く活性化させ、そして不快な出来事を回避させるという行動をとらせることになる。つまり、叱られれば不快になるので、叱られないように行動をすぐに変えていくことになる。

この叱りによるNegativity Biasの力を私たちは日常の中で知らず知らずのうちに体験してしまい、ついには「叱って人を動かす」ことが効果的であるということを学習してしまう。なぜなら、叱って相手の行動を変えることができると脳内にドーパミンが放出され、成功体験=快感として脳内に刻まれる。すなわち覚醒剤と同じ働きが発生することになる。そして「叱らずにはいられなくなる」という「叱り中毒(叱り依存)」が発生することになってしまう。このNegativity Biasが今日問題になっている暴力的指導やパワハラの基本的な脳内のメカニズムになっている。

2.叱りが生む「セリグマンの犬」

叱りは、Negativity Biasという強力な暗黒の力(まさにSTAR WARSのダースベイダーのように)を持っている。その力によって、叱られる方は死に物狂いで叱られないように行動を変えてくる。結果として、叱られる方の人間のパフォーマンス(競技成績や学校の成績など)がある程度上がってくる。叱る側の人間はそれを見て「叱ればパフォーマンスがあがる」ことに快感を感じ、さらに叱るという「叱りの無限ループ」に陥ることになる。

では叱られ続ける人間の方はどうなるのだろうか?その答えは「セリグマンの実験」が参考になる。セリグマンという研究者は、犬を動けないように拘束し電気刺激(=叱り)を与え続けるという実験を行った(今では倫理的に問題になりとても行える実験ではない)。最初の段階では、犬は電気刺激を回避するために逃げようともがくが、それでも電気刺激を与え続けると、やがて無気力になり電気刺激に対して何も回避行動を取らなくなる。そしてただひたすら無抵抗に電気刺激を受け続けるようになる。さらに、拘束を解いて逃げることができるようになっても、逃げようとせず無気力に電気刺激を受け続けてしまうようになってしまう。これは、犬が「自分は無力である」ということを学習し、この「学習性無力感」によって無気力な状態になってしまうためだと考えられている。

叱るという行為は、その暗黒のパワー(Negativity Bias)により、素早く行動を変化させる。しかし、叱るという行為を多用すると叱られた方は「セリグマンの犬」になってしまい、無気力な状態に陥ってしまう。つまり、今でいう「うつ病」の状態になるということになる。叱ることは、簡単に相手の行動を変えられる。しかし、確実にやる気を奪っていき、無気力なセリグマンの犬を育てていくことになる。

この話をあるスポーツ種目の指導者講習会でした後に、受講者の感想に書いてあったコメントが今でも忘れられない。「私はセリグマンの犬でした。」

1. Why Do People Scold Others? –Brain Mechanism of Scolding Addiction–

Why do human beings scold their children or other people? The reason is that the act of scolding exerts a remarkably strong influence on changing another person’s behavior. This powerful effect is known as the Negativity Bias.

For example, imagine two situations: one in which you receive 100 dollars and another in which you lose 100 dollars. Since the amount of money is the same, one might assume that the emotional impact should also be equal (though the emotions themselves—joy vs. sadness—differ in quality). In reality, however, the negative event of losing 100 dollars produces a much stronger emotional response than the positive event of receiving 100 dollars. This tendency for negative events to have a greater psychological impact than positive ones is called the Negativity Bias.

In our experiments using fMRI, a device that makes brain activity “visible,” we found that negative stimuli such as scolding activate the brain’s emotional center—the amygdala—more strongly and more rapidly. In contrast, positive stimuli such as praise activate the amygdala only weakly and slowly. Thus, negative information such as scolding activates the emotional center quickly and powerfully, prompting behavior to avoid unpleasant experiences. In other words, because being scolded feels unpleasant, people immediately change their behavior to avoid being scolded again.

Through repeated exposure to the powerful effects of this Negativity Bias in everyday life, people unconsciously learn that “scolding others to make them move” is an effective way to change behavior. When a person succeeds in changing someone’s behavior through scolding, dopamine is released in the brain, producing a sense of success or pleasure. This neural mechanism functions in a way similar to that of addictive drugs, reinforcing the behavior. As a result, the person becomes unable to stop scolding—developing what can be called “scolding addiction.”

This Negativity Bias forms the fundamental neural mechanism underlying today’s issues of violent coaching and power harassment.

2. The “Seligman’s Dog” Created by Scolding

Scolding possesses a dark and powerful force—like Darth Vader in Star Wars—because of the Negativity Bias. Driven by this force, those who are scolded desperately try to change their behavior to avoid being scolded again. As a result, the performance of the scolded individual (such as athletic or academic performance) may temporarily improve. Observing this, the person who scolds experiences pleasure in seeing performance increase, becomes convinced that “scolding raises performance,” and falls into an endless loop of scolding.

But what happens to those who are continually scolded? The answer can be found in the classic experiment by Martin Seligman. In this study—an experiment that would now be considered unethical—dogs were restrained so they could not move and were repeatedly given electric shocks (a metaphor for “scolding”). At first, the dogs struggled frantically to escape the shocks. But as the shocks continued, they eventually became apathetic and stopped trying to avoid them. Even after the restraints were removed and they could escape, they did not try to flee, remaining passive and accepting the shocks.

Seligman concluded that the dogs had learned helplessness—they had learned that they were powerless, and as a result, became completely passive.

Scolding, driven by the dark power of Negativity Bias, can quickly change behavior. However, when used excessively, it transforms the person being scolded into “Seligman’s dog,” producing a state of helplessness and apathy—essentially, what we now call depression. Scolding may be an easy way to change someone’s behavior, but it inevitably erodes motivation and cultivates helpless, unmotivated “Seligman’s dogs.”

After I presented this story at a coaching seminar for sports instructors, one participant wrote a comment that I have never forgotten:

“I was Seligman’s dog.”